Image credits : Wikimedia Commons. Modified by Jen Wike Huger.

(This was originally posted on Opensource.com, thanks to their editors and to Mark Charmer for getting the writing into good shape.)

Open data and going digital are subjects high on the international agenda for global development, particularly when it comes to financing improved services and infrastructure for the poorest people in the world. Young people from Laos to Lagos aspire to become software developers, and smartphones are set to put unprecedented computing power into every corner of the earth. But the paradox is that many governments still only have rudimentary information technology infrastructure and often can’t find trained and skilled staff to design and run it.

In many African countries, the capacity for central and regional government to work with digital tools is limited because it is common to find only a few people in the government department responsible for coordinating involvement and investment in, say, rural drinking water infrastructure and financing. Thus, they are easily stretched thin by the demands and the need to be experts on many aspects of IT and data systems.

Our organization designs and builds open source data systems, which we also run as Software as a Service (SaaS), for organizations working with international development. This embraces a fascinating mix of multi-lateral organizations (such as Unicef and the World Bank), international NGOs, and central and regional governments. This is a pivotal moment for the development of country governance tools. I’ve long felt that the roots of such systems should be built on open source software because in just a few years’ time, IT infrastructure in a country will be just as important as other infrastructure, such as roads or water supply. Our societies are evolving toward a future that is intricately connected with efficient just-in-time systems that keep our society ticking, and IT is a vital part of the system. For the more than three billion people living in Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia—areas with under-developed IT infrastructure for governance—a big change is coming quickly.

For a little more than two years, we have been helping governments of countries like Ethiopia, Nepal, Nigeria, and Indonesia with map infrastructure for schools, health centers, public drinking water points, and peri-urban water connections. Access to these data systems quickly changes the way infrastructure investments are done. Without the systems, making effective investments and prioritizing decisions is difficult, if not impossible. For example, full-country rural drinking water inventories are underway or complete in Ghana, Benin, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Mauritania, and other countries.

So why is open source software important in this context? I believe that a strong society has a common ownership of its critical infrastructure, and IT services that support governance of municipalities, regions, and countries are becoming critical infrastructure.

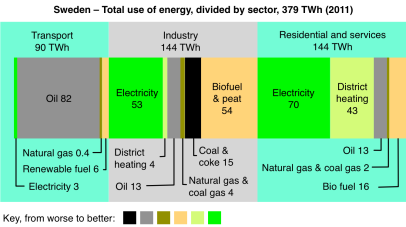

Where I live, my local municipality owns or controls the piped water supply, sewage system, local roads, electricity network, waste management facilities, fiber-optic network, and district cooling and heating network. Companies offer services that use the roads, fiber-optic, and electric network, or provide management and operations of the waste and heating/cooling facilities, but ultimately the infrastructure is under the control of the municipality and, as such, is indirectly owned by the citizens.

IT infrastructure, including software and databases, will become just as important as other infrastructure, and the best way to retain control over your IT infrastructure is going to be to work with open source software. With open source software, the door is always open, too, so if you want to move your data operations, you can take the software and your data with you. Ideally, the result will be better governance, better democracy, and ultimately better lives for the populations of these countries in the future.

Filed under: Open source

Comments